14 December 2018

extended: 30 April 2022, reviewed 17 September 2024

THE ORIGINS OF THE EASY TOWN IDEA

The call came on a Sunday in April 2012.

My friend Easy was in a critical condition after an aneurysm had ruptured in his brain.

About two weeks later, I left Berlin for a small town in southern Germany and booked a room in a B&B. Some of Easy’s family were there too.

We visited Easy several times a day.

At first, he was still in an induced coma. When he finally woke up, he couldn’t talk, eat or walk.

The seven neurologists in the intensive care unit offered seven outlooks on Easy’s case, ranging from no hope at all to he will be fine again, given time.

After another surgery and more time in intensive care, Easy was transferred to a rehab clinic. Since he didn’t recover fast enough (according to his healthcare insurer), he was transferred again. This time to a nursing home.

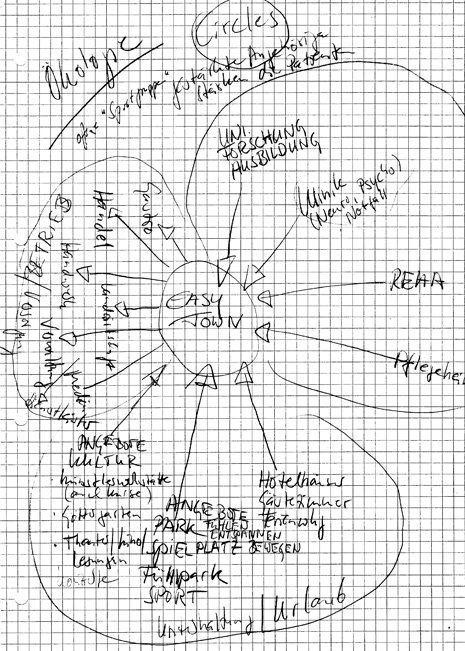

It was during my visits to the rehab clinic that the idea for an Easy Town was born. I felt helpless and frustrated, so my brain got busy with finding solutions.

My main question was: How could the situation for the neurological patients and for their friends and relatives be improved?

I will give you three examples of the thoughts that came up.

by Charlie Alice Raya, 2012

1) RELATIVES AND FRIENDS OF PATIENTS

It’s not like the hospital staff wasn’t friendly, but actual support for relatives and friends was missing.

How could this be addressed?

Looking at my own situation, I thought, well, I need a place to sleep, a job to finance my stay and some distraction.

So, if a patient were treated in Easy Town and far away from home, relatives and friends could get an affordable accommodation, a place for their kids in school, and a job.

This way, families could support the patient without financial stress and with local support.

To make this work, the town would need business diversity and flexible job models. And some good recreational offers as well as a support network.

2) A SEPARATE PLACE FOR EACH GROUP

One of the things that struck me most was the isolation of everyone involved in the recovery process.

It seems typical for our time (at least in western societies) that everyone has their exclusive shut-away place.

Toddlers are in the nursery, kids at school, adults at work, the ill in hospitals, the disabled and old in nursing homes.

There are only few spaces left where generations and people of different constitutions and walks of life mingle.

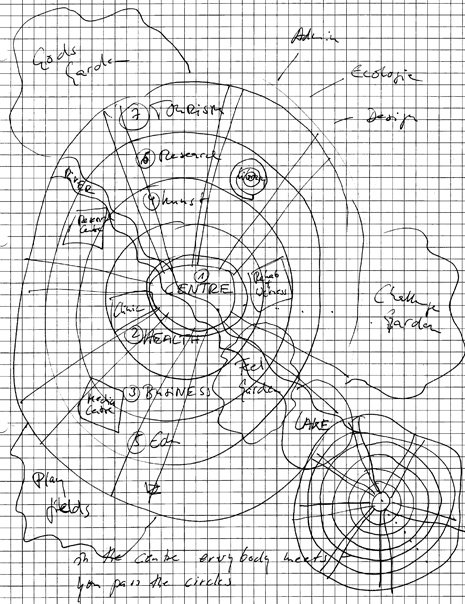

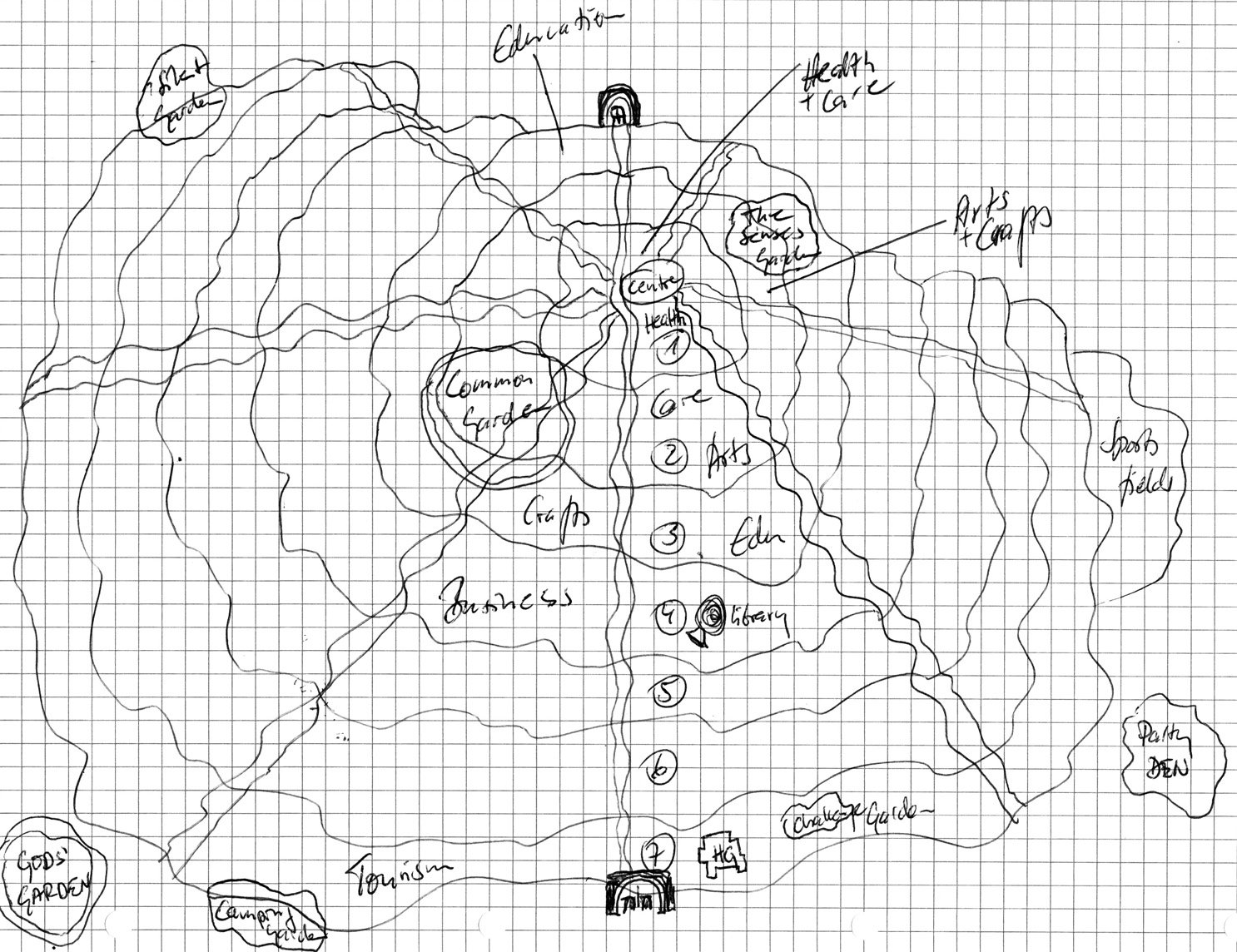

Wondering how this point could be addressed, I started to imagine a town centre which would offer opportunities for patients to interact: things like access to theatre rehearsals, giving a hand in a bakery, or sitting in a cafe and watching the buzz on the town square while chatting with a stranger. This way patients and relatives could be part of the everyday life in town.

And I thought that tourists might add to the picture.

To make tourism work, the town would need architectural highlights, gardens worth visiting, recreational offers, museums, workshop …

And the town would need a magic of its own.

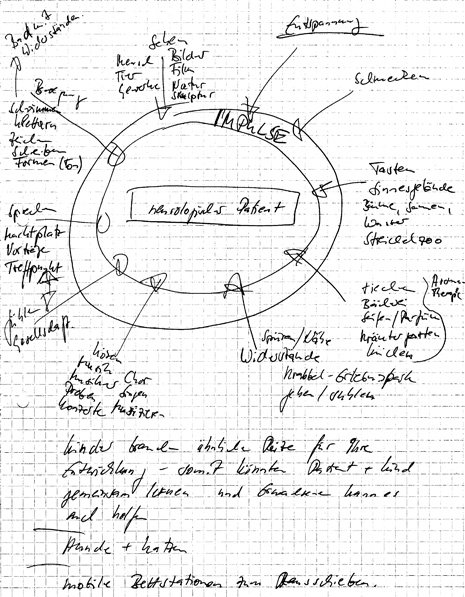

3) STIMULI FOR THE BRAIN

A person who has suffered from a stroke, or a person who is dealing with a depression, can do with a lot of positive stimuli, be it sitting in the sun and smelling the freshly baked bread, or rolling into an artist’s studio with a wheelchair and watching a new piece of art emerge, and maybe even adding a splash.

While the brain needs rest, it doesn’t need extended boredom or too much time to worry.

It needs stimuli, positive encounters, the notion of being useful, the notion of having some self-control, the notion of being part of something.

These points could be addressed in the way hospitals are run, how the arts are integrated, and how much access the patient has to something like a normal life.

And then there is the idea of The Senses Garden …

HOW TO FINANCE SUCH A TOWN?

Pretty soon, my business and economics background kicked in, and I asked the obvious question: How to finance such a town?

I was already playing with the idea that tourism might be a way to co-finance healthcare if tourism was run by the town.

By now there are additional ideas, and then there is this thought that came up for book 4/1, building:

‘You know how people tend to say: “But who will pay for all this?” I thought about it, and I came to the conclusion that from now on my response will be: “So long as you find the money for subsidies, state receptions, the entertainment industry, the military, or for bribes for political and economical gain, and for all the other kinds of ambiguous expenses, I will not think about this question again.” And I might add: “Probable fun fact: if we build our town and do a good job with our experiments, then many government expenses won’t be necessary any more.”’

notes for book 4/1, building

IS EASY TOWN AN UTOPIAN IDEA?

No.

‘It doesn’t take rocket science to do better for ourselves, our fellow humans and our planet. Besides, there is nothing utopian about asking questions and testing ideas.’

book 3, shaping

And with a town experiment, we could base any new approach regarding business practises, society, ecology, arts, healthcare, and all other areas, on research results.

One of the things, I love about the easy town story is that it provides the perfect playground to rethink and question everything, and to test new ideas, without getting caught up in any ideology or polarisation or superiority complex.

It’s practical and down to earth. And on earth.

WHO HAS THE TIME TO BUILD A TOWN EXPERIMENT?

Since we have time for space exploration, I don’t see why we can’t make time to solve some problems here on planet earth.

WHAT HAS CHANGED SINCE THE ORIGINAL IDEA EMERGED?

The easy town idea started with a clear focus on the neurological patients and their relatives.

By now, the story and the ideas involved are a lot more complex and take nearly every aspect of life into account.

Some of the major questions are: How to create an environment that is healthy for humans? How to build and live as part of the planet’s ecosystem? What is at the roots of the troubles and anxieties we are facing or trying to ignore?

‘That’s one of the big troubles. It’s so easy to say: oh, we have to fight climate change, let’s go big into renewable energy and all will be fine. It won’t. If we don’t rethink the way we do business, how and where we produce and farm, how and what we consume, how and where we build, how we live and let live, then all the renewable energy of this world won’t do a thing for our survival.’

book 3, shaping

DIG DEEPER

The following is a dialogue from book 1, beginning where Alice, the main character, tells Tom, a billionaire, how the idea for easy town came about.

book 1, beginning

by Charlie Alice Raya, 2012

‘Why is the name so important? It’s not a very good name.’

‘Easy is a friend. His story inspired the initial ideas for the project. That’s why the name is essential — to me.’

(…)

‘So, what’s Easy Town about?’

Alice Adler seemed to relax. She put the copy of the agreement back into her folder. Then she inhaled and said: ‘To understand where the ideas come from, it’s best to start with what happened to Easy.’

Tom nodded.

‘Easy was a friend who went through several medical facilities after an aneurysm ruptured in his brain. When he woke up from the induced coma, some two or three weeks after the initial operation, he couldn’t speak, walk or eat.’

Alice Adler paused and a faraway smile appeared on her face. ‘He kissed my hand after I cut his fingernails. That was when I knew that he was still there, somewhere.’ She inhaled. ‘While he couldn’t smile, he could express dismay. And usually, he was dismayed. Who wouldn’t be?

His condition got worse after an operation to close his skull. You probably know that a bit of skull is removed to operate on the brain and to relieve the pressure that is caused by swelling. In my unqualified opinion, this second operation was undertaken too early. But apparently, the clinic followed some specifications by his health insurance company. The insurer wanted to see him off to rehab as soon as possible and argued that the missing bit of skull needed to be replaced to prevent injuries during rehab. Other insurers seemed to handle this differently, since there were patients with missing skull bits in rehab. But I might not know the full story.

In rehab, he didn’t improve as fast as the insurance guidelines demanded, and eventually he was transferred to a nursing home where little would be done to improve his mobility or anything else. You could say, he lay in wait for the inevitable.

I had little income at the time. And I live in Berlin while he went through several facilities in Southern Germany.

There was only so much I could and would do for him.

When I visited, I usually stayed for four days. It always frustrated me that I could see progress during my stay, but the next time I came, I had to start from scratch again.

The measures specified by the health insurance company obviously weren’t sufficient. No worse. They didn’t even manage to maintain the progress Easy and I achieved together. I won’t get into the details of these visits, but I’ll point out the observations which influenced the project ideas; ideas I started to write down during my visits.

The brain. The brain is an incredible organ. It has enormous potentials of healing itself or of finding alternative routes to achieve something that has become impossible due to an injury. I read about a girl who lost half of her brain and made a full recovery. Apparently, recovery becomes more difficult the older you get, but a lot can be reignited if the brain receives enough stimuli, especially if these stimuli are accompanied by emotions and the sense of doing something relevant, as I observed.

For example: During a visit in the nursing home, I saw that Easy’s wardrobe was in a mess. So I decided to tidy it up. While doing so, I would pick up a cap or his sunglasses and hand them to him. He would hold them until I had cleared some space on a shelf. These were just small activities: receiving, holding, handing back. But I could see that these relevant activities were a lot better for him than me just sitting by his bedside.

Relevant activities became a key point in my considerations. For example: when he was still in rehab, I sometimes watched other patients in the communal area, a circular space on the sixth floor of the clinic, with the elevator in the middle. I remember a man who could roll around in his wheelchair, using his legs to move forward. He spent hours circling around that elevator. And I thought, it would be much better for him if he had somewhere to roll to. Going outside wasn’t an option since the clinic was built on a steep hill. But what if the clinic was next to a village centre, and he could roll into the bakery, even give a hand in the bakery or roll into an artist studio and hand the brushes to the artist or roll into the stables and meet the stable master? What if there was some kind of feel garden, where he could roll through a number of stimuli: feel running water, feel hay, feel fur, feel heat, smell flowers, hear birds, you name it. Anything really that gives the brain a stimulus, pleasant or not.

Thinking along those lines, I remembered how Easy liked to go to a runnel in a park. He would sit there and dangle his feet in the water. So what if the relatives of patients could tell the clinic about such preferences? What if patients could experience things they like? It would be no problem to build a platform on a jetty which could be lowered into the water, and the patient could do some dangling while sitting in a wheelchair.

This takes us to another important aspect: self-determination.

In a hospital, every patient is pretty much treated the same way. All patients have the same kind of room, and not a room they would choose to live in. All patients have to follow the same daily routine, and not the routine that fits their biorhythm. Usually patients have no access to things they like to do. Worse than that, a patient like Easy has nothing left where he could make a single decision on his own, let alone do anything on his own.

At the time I thought, for example, what if I could build a little mobile table and fix it to his bed? And then he could pull the table towards him or push it away. A table with many buttons, because he loved electronic gadgets. A light could be fixed to the table which would allow him to decide when to turn off the lights. And maybe some sort of boxes or pockets could be added with paper and pencils. And when no one is watching, he could try for himself whether he can’t will his brain to overcome the barriers. Of course, there is a danger of self-harm, since the patient isn’t in full control. But I’m sure, we could find a way around that. The treatment I saw never took embarrassment into account nor our impulse to try out things when no one is watching.’

Alice Adler paused and looked out of the window, towards the lake. ‘I remember looking into his eyes at the nursing home. It felt like looking into a deep tunnel, at the bottom of which, he was standing, waving his arms, shouting, jumping up and down, trying to say something. But he couldn’t get it out. He couldn’t get out.’

Alice Adler inhaled and looked at Tom again. ‘Another observation was that all these patients were shut away. Life in any hospital is a life centred around illness. And I thought about our society’s tendency to divide people into groups. The sick are in hospitals, the old in old people’s homes, the children in kindergarten or school, the adults at work. Only a few paths cross. And I wonder whether that’s a good thing. It didn’t seem like a good thing for the patients or their relatives.

For me, the time spent with Easy had many pleasant moments, insofar as it was good to watch his progress. The worst part of the day was the evening. I would sit alone in my B and B, not knowing what to do with myself, my thoughts circling around Easy’s situation. Going to a bar alone didn’t help.

And that brings me to another relevant point. During the day, I sometimes got talking to the relatives of other patients. In particular, I recall a wife whose husband was paralysed after a spine surgery. Contrary to Easy, he showed no reactions at all. She told me that she came all the way from Frankfurt, which took her maybe two hours by train, and that her holiday entitlement was down to ten days. Yes, she had tears in her eyes when she said: “I don’t know what to do after that. I’m a waitress. I don’t earn enough. I can’t afford to come here or to lose my job.”

And again, I thought the village idea could help. I only had to extend the idea to include the needs of the relatives of patients. So what if there was a village that offered all kinds of stimuli, relevant activities and self-determination for neurological patients, and dissolved at least some divides in society, and also offered jobs to relatives or friends so that they could stay close and still earn a living, still have a life?

So I started to think about businesses which can easily work with temporary staff. And that brought up the question of what a useful business diversity for the town could look like. The latter is important for the next point too.

During my visits, I learned more about the enormous costs involved in running a hospital. And since I have no interest in a luxury hospital or village, I wondered how the clinics in such a village could be run feasibly, without issuing exorbitant healthcare bills. This point opened a whole new box of questions. For example: could tourism help to finance the town’s healthcare services? Or what kind of business diversity would provide the town with stable finances? But also: could costs be reduced if there wasn’t such a dependence on big pharma companies, and can we rethink the way hospitals are run?

And lastly, for now, the nurses and doctors.

I couldn’t stand the amount of seriously ill patients for more than four days at a time. And I often wondered how nurses and doctors managed to cope with the misery. Taking this into account, I asked: what if this village offered temporary alternative jobs for medical staff too? A temporary change in occupation is bound to have a positive effect and would probably prevent some burnouts.’

Alice Adler straightened in her seat. ‘Well, now you know what got me started. I soon realised that a village would be too small to make anything like this work. And once I started to think about a town, all other aspects of our economic and social life came into view. And more issues surfaced where alternative approaches could be useful. In fact, I haven’t found a single issue that couldn’t do with a rethink.’

Alice Adler paused briefly. ‘So, what I’d like to propose is to build a town from scratch and run it as an experiment. In the experiment, we would treat every aspect of life as a variable, as something we can put to the test, as something we can adjust until it makes more sense than our present systems. We would question every theory we know. We would question how we do business, how patients are treated, how the town is composed in terms of people, businesses, educational and cultural offers, or its layout. And we would try to find out whether we can’t do better if we use our imagination, and hang our complacency in the closet.’

‘And turn the world upside down?’ Tom asked while finishing a note.

‘Just to give it a good shake,’ she replied, and he could hear a smile in her voice.

Her next words, however, were spoken quietly. ‘My friend Easy was not fine. Many of us on this planet are not fine. But maybe we could be.’

Tom swallowed and looked up from his writing.

But her eyes had a note of cheekiness in them. She had all these questions and saw the misery, but she wanted to do something about it, not dwell on it.

book 1, beginning